It is critical that you know which specific C57BL/6 substrain you are using so that you use the appropriate controls for your experiments and interpret your data correctly! Since C.C. Little (the founder of The Jackson Laboratory) initially generated the C57BL inbred strain in the 1920’s-1930’s, the inbred substrain C57BL/6 became the most frequently used mouse strain in biomedical research. The popularity of C57BL/6 inbred mice led to the establishment of many colonies at different vendors and academic institutions around the world.

C57BL/6 substrains

You may not know this: every time a new C57BL/6 colony is maintained separately from an existing colony for 20 or more generations, it becomes a new C57BL/6 substrain. The generations are cumulative, so if each of the two separate colonies breed for 10 generations (~2-3 years), they are 20 generations apart, and different substrains with potentially different phenotypes. As part of a strain’s nomenclature, Laboratory codes are added at the end as the substrain designation. C57BL/6J is the parental substrain; “J” is the laboratory code for The Jackson Laboratory. Therefore, there is no source of “C57BL/6” mice; there is always a longer designation for each substrain indicating the institute or laboratory that maintains the different colonies.

C57BL/6 substrains are not the same!

Once a new C57BL/6 substrain is established, spontaneous mutations will arise in both the original colony, and the new colony. A subset of those mutations will spread through the colony by genetic drift and become fixed (homozygous in all mice). The longer individual substrains are separated from each other, the greater the number of genetic differences between them. These genetic differences can lead to phenotypic differences.

C57BL/6J vs. C57BL/6N

In 1951, C57BL/6J mice were sent to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) where a colony was established and was called C57BL/6N. Subsequently, many substrains have been derived from the C57BL/6N colony. A mutation that causes spotty retinal degeneration, known as Crb1rd8was discovered to be homozygous in all C57BL/6N related substrains, but is not present in the C57BL/6J substrain. Additionally, data collected from the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) phenotyping centers has found numerous phenotypic differences between the C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N substrains.

The dangers of falling into the ignorance trap

There can be serious consequences if you are not fully aware of the genetic background (strain and substrain) or your experimental mice. You wouldn’t be the first researcher to fall into this trap. When you choose the wrong control strain, you have a high risk of misinterpreting your data, reaching faulty conclusions and seriously delaying your research program.

Our blog post, “Why it Took 2 Years for a Harvard Research Lab to Get Back to Research” describes how a research lab accidently associated an immune deficiency phenotype to a knockout allele when in fact it was a due to a mutation in the particular C57BL/6 substrain the knockout was backcrossed onto. The error was discovered when the knockout model was backcrossed to a C57BL/6 substrain from a different vendor, and the phenotype was lost. Most of the time, effort, and resources used to elucidate why the team couldn’t replicate previous results could have been saved if the authors had used control mice with the same genetic background-as the one used to backcross the knockout model of interest.

Is this gene protective or toxic?

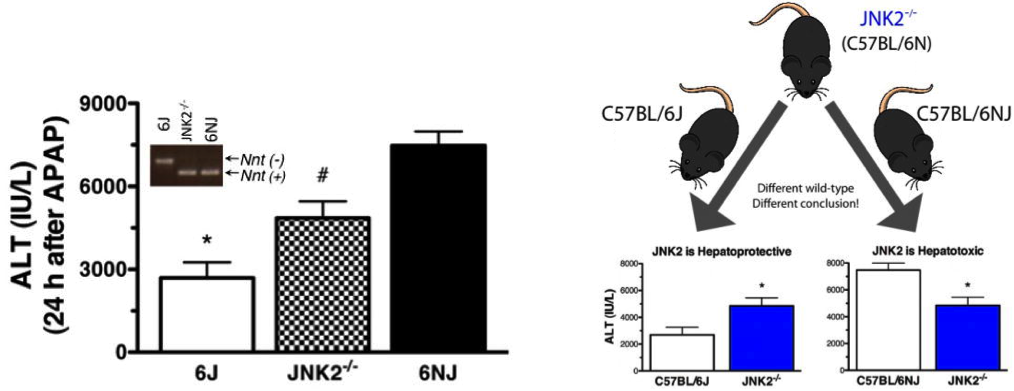

Another notable example comes from a laboratory at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (part of NIH). After testing the effects of a Mapk9 (Jnk2) knockout on acetaminophen-induced liver injury using C57BL/6J as wild type controls, the results were contrary to expectations. When repeated using C57BL/6NJ (C57BL/6N imported into JAX from NIH in 2005) as wild type controls, the phenotype of the Mapk9 knockouts fell squarely in between the phenotype for the C57BL/6J and C57BL/6NJ (see Figure).

The researchers found themselves in a situation where they could interpret their data in two opposing ways, depending on which control was used. If the used C57BL/6J as the controls, then the data indicated that MAPk9 was hepatoprotective. If they used C57BL/6NJ as controls, then MAPK9 seemed to be hepatotoxic.

Figure 1. Data conclusions differ depending on control strain selection. Mice were treated with acetaminophen (APAP, 300 mg/kg intraperitoneally). Liver injury was assessed 24 hours after treatment by measurement of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity.

Fortunately, the researchers were able to determine that the Mapk9 knockout was on a C57BL/6N background, and concluded that the gene was hepatotoxic. However, think how easily this data could have been misinterpreted and how often such mistakes get missed completely, leading to unreproducible results!

Therefore, be forewarned and make sure that you know not just the inbred strain, but also the substrain of mice you are using for experiments so you choose the right controls and produce reliable meaningful data. Remember, there is no such thing as a C57BL/6 mouse strain, there is always a longer name to it!